Ancestral Threads

Ancestral Threads - piecing the patchwork

I remember the morning I got news of Nana Mary’s death. Curled up in the warmth of my bed, mum told me she’d died of a heart attack during the night. This news hit like a bleak snowstorm harsh enough to kill me. My throat tightened. I had no words. My heart felt like it might stop from the ache, and my world instantly became more insular in the absence of motherly support in my grief. My teen years of anorexia thereafter held a silent, yet deafening sense of loneliness. Isolation in my room attacking academia became my solace and drug to numb the pain.

The hotel room, with a half-drunk bottle of Kahlua and packets of pills next to the bed, was the culmination of those nine painful years of emotional hunger. But I awoke to vomit on the crisp bedsheets, now soggy with tears. Deep shame flooded me. I was alive and had to live to tell the tale, but it went largely untold, especially to my family, who sought answers as I lay in a psychiatric hospital bed. “Trust God,” my parents said. I needed comfort and cuddles, not Christian platitudes.

The shame deepened because this hospital was the workplace where I had offered solace, compassion, and witness to others’ pain. Yet the system medicated and didn’t offer balm to a hurting soul. With hindsight, the timing of my “attempt” was not “au hazard”. It was the anniversary of the death of my nana who gave me the warmth of unconditional love I had been craving for in the absence of it on earth. Soul hunger, not suicidal ideation.

Years later, at the French Film Festival, I watched Annie Colère, the true story of a mother who accidentally became pregnant. She joined the underground movement of doctors and women in 1970s France who performed illegal, but safe abortions in public view to push for legalisation. A wave of nausea came over me. I fainted. The abortion scene took me viscerally to memories of the story of Nana Mary housing women in Dunedin who sought backstreet abortions in that era. Like me, she was a deep carer guided by a social conscience and service heart.

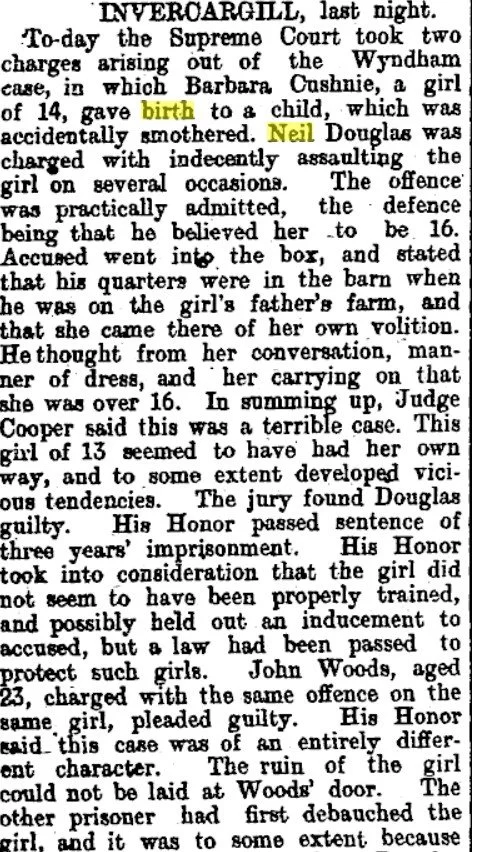

Her mother too, as a teen was raped by two workers on the family farm in the early 1900’s in southern NZ. Her baby was found smothered, and the newspapers labelled her as “not properly trained.” She later birthed my nana, then disappeared, abandoning her forever, consumed by grief and shame. The film also took me back to my early teens to an internal examination. I didn’t yet know my womany body parts. It was painful, scary, invasive. A violation. A Dutch nurse suggested I hold her hand. I gripped it until her veins protruded.

It’s no wonder I’m drawn to stories of umbilical cords and maternal bloodlines. I’m a bold woman who speaks - telling stories so curses be broken and trauma healed. My voice, like my ancestors’ and Annie’s, is the medicine.